Housing providers must navigate a delicate balance when it comes to eviction—ensuring the financial stability and safety of their properties to support long-term operations for all of their residents and, at the same time, determining when it’s possible to provide alternative options for residents facing periodic financial hardship.

Striking this balance is especially challenging given the potential unintended consequences of eviction regulations, as well as the difficulty in collecting accurate data about evictions. While eviction is a difficult and costly process for all involved and typically used as a last resort, it is ultimately the only tool available to rental housing providers to enforce the contract between them and their residents. As such, collecting eviction filing data does not tell us much, or anything, about the housing providers’ operations, but may be more effective in identifying financial instability or other struggles in the household.

This piece focuses on two aspects of the national discussion around evictions—efforts to define how many evictions are occurring and the policy decisions that have been driven by these efforts.

Types of Evictions

The eviction process can be generally described as:

Lease violation such as Nonpayment of Rent ➜ Request to Remedy or Notice from Housing Provider ➜ Eviction Filing ➜ Court ➜ Enforcement

A resident may move out of a unit after an eviction has been filed but before there has been a judgment. On the other hand, they also could repay the late or missed rent. In both cases, that means that an eviction judgment would never occur, however it would create costs for a housing provider, including court fees and unrecovered rent.

Examples like these highlight the challenges of interpreting eviction data, including reasonable disagreements over what qualifies as an eviction and gaps between what the data captures and the actual housing displacement it aims to measure.

Efforts to Learn About the Number of Evictions

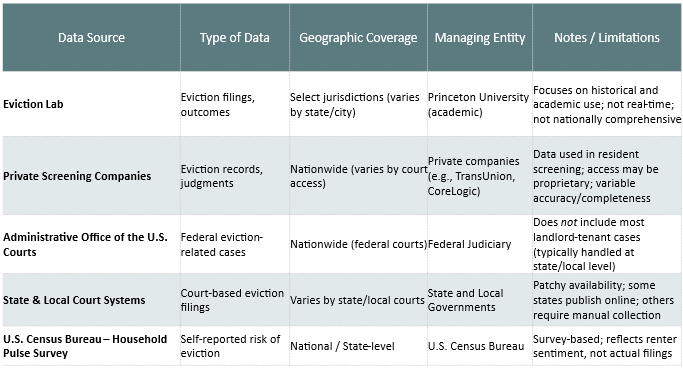

Multiple efforts have been made to aggregate data from eviction filings and judgments, however, none of them are truly accurate. Many of these efforts were profiled in a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report which, under the directive of The Explanatory Statement for the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, documented and assessed the constraints of current eviction data collection efforts. The figure below provides information on many of the data sources currently available:

The court systems are the logical source of eviction data, however, the setup of the legal system is varied. Each state has its own individual court system with its own unique database which is often the case for jurisdictions within the states as well. There is no aggregated search mechanism for all these systems. In many cases, there are no publicly available digital search options.

There are also not common terminologies between jurisdictions. The options for the eviction filing given may be completely different in one jurisdiction than another, making it difficult to determine any discernible pattern.

Additionally, a large amount of the underlying data relies on a model to account for the jurisdictions where no data are publicly available. As a result, members of the public not familiar with research methodology may assume an estimated number to be exact.

Numerous local research organizations and media sources have also attempted to gather eviction data at the local level without complete success. The RVA Eviction Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University, in partnership with the University of Virginia’s Equity Center, created the Virginia Evictors Catalogue using a similar methodology to Eviction Lab. For many years, the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority appeared high on the list of owners filing evictions, suggesting evidence that evictions are simply a symptom of an underlying deep income problem for renters. This is true of many public housing authorities across the country who often serve lower income households with the least amount of income stability.

Attempted Eviction-Related Policy Interventions

Even in the absence of accurate data, many jurisdictions have attempted to limit, delay and otherwise create regulations designed to decrease or prevent evictions, without understanding that eviction is more of a symptom of a household that needs support. For example, numerous states enacted eviction moratoria related to the Covid pandemic, which had varying levels of requirements regarding eligibility and documentation, partial rent payment and repayment for back rent, and notification procedures. However, differing options were available for emergency rental assistance, which would have protected renters in need without the unintended consequences of extended suspension of evictions.

Policymakers have also created regulations that limit the ability of housing providers to carry out an eviction, enacting laws such as enhanced “notice to vacate,” “just cause” or other requirements. Such policies can regulate how and when housing providers can notify a resident of their intent to file an eviction, how much notice must be given before an eviction filing, or a ban on non-renewals without a reason.

Impact on Housing Providers and Residents

There has been a variety of research on the adverse effects of evictions on renters. Much of this research has focused on their wellbeing, with documented declines in physical and mental health for households at risk of eviction. Academic research suggested that eviction moratoria did improve stability for households at risk of eviction. But additional research has indicated that this stability was temporary and did little, if anything, to address underlying problems within the household’s circumstances that led to them facing eviction.

There is relatively little information about the impact of evictions and moratoria on housing providers. In both formal and de facto eviction moratoriums, the outcome is the same: rent goes unpaid. The National Equity Atlas estimated a total rent debt of $9.8 billion as of September 2024. This unpaid rent creates financial strain for housing providers and, in turn, residents living in rental housing communities, limiting the ability of housing providers to properly maintain properties in some cases. Unpaid rent debt has spillover effects in housing providers’ financial ability to maintain their property. Research by MetroSight on behalf of the National Multifamily Housing Council and National Apartment Association provides some insights: properties located in jurisdictions with “good cause” regulations had significantly lower revenue and higher operating costs. Follow-up research also showed that eviction laws are associated with higher rents. Further, not all unpaid rent is a result of a struggling household: a survey of housing providers also found an increase in fraudulent applications, which frequently results in nonpayment of rent once the unit was occupied. Fraud creates even more of a financial strain, as providers are forced to invest in screening software to attempt to mitigate their risk.

Further Research Opportunities

Much of the focus of research related to evictions has focused on quantifying the number of evictions, but debates about what the definition of an eviction is or how many evictions are too many dilute the fact that for every eviction due to nonpayment of rent, there is a household facing financial instability and a housing provider that is faced with increased costs that indirectly impact renters in that community.

Correlation does not necessarily mean there is causation, thus even if we could accurately discern the number of evictions, it does not necessarily mean that housing providers are doing anything wrong. More research on the current financial situation of both rental households and housing providers is needed. This will allow policymakers to enact more targeted solutions that actually help renter households in need and not just delay assistance or cause other problematic results for housing providers and other renters in the community.

Caitlin Sugrue Walter, Ph.D., is SVP and Head of Research and Innovation, with primary responsibility for overseeing NMHC's research efforts. Additionally, Caitlin is an active member of the National Association for Business Economics, a member of Up for Growth’s Advisory Board, the Research Institute for Housing America's Industry Advisory Board, and is a member of the Eastern Panhandle Advisory Council for Girls on the Run of the Shenandoah Valley. Prior to working at the Council, Caitlin was an analyst at a real estate advisory firm. Caitlin has a B.A. and B.S. (Planning and Public Policy, Criminal Justice) from Rutgers University. She also holds an M.A. in Urban and Regional Planning, a certificate in Nonprofit and Non-Governmental Organizations Management, and a Ph.D. in Planning, Governance and Globalization with a concentration on metropolitan economies and development from Virginia Tech.

Caitlin Sugrue Walter, Ph.D., is SVP and Head of Research and Innovation, with primary responsibility for overseeing NMHC's research efforts. Additionally, Caitlin is an active member of the National Association for Business Economics, a member of Up for Growth’s Advisory Board, the Research Institute for Housing America's Industry Advisory Board, and is a member of the Eastern Panhandle Advisory Council for Girls on the Run of the Shenandoah Valley. Prior to working at the Council, Caitlin was an analyst at a real estate advisory firm. Caitlin has a B.A. and B.S. (Planning and Public Policy, Criminal Justice) from Rutgers University. She also holds an M.A. in Urban and Regional Planning, a certificate in Nonprofit and Non-Governmental Organizations Management, and a Ph.D. in Planning, Governance and Globalization with a concentration on metropolitan economies and development from Virginia Tech.